The weekend of January 21st and 22nd saw my first academic conference attendance. An exciting, slightly terrifying, but ultimately very rewarding experience. The Society of Musicology Ireland and the International Council for Traditional Music Ireland jointly hosted this Postgraduate Conference in University College Dublin, on the 21st and 22nd January 2023.

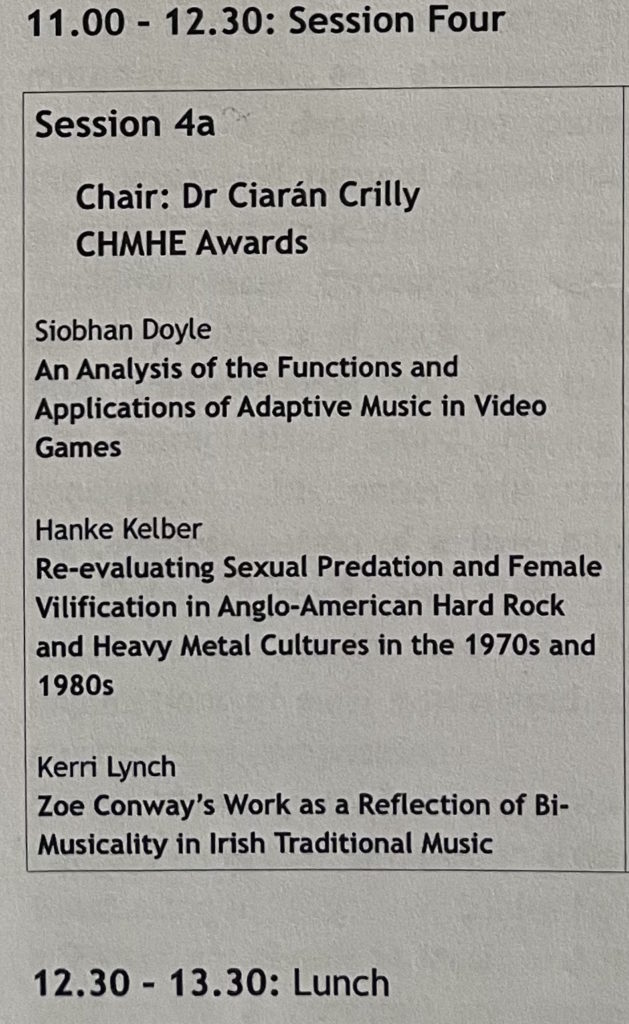

I had the pleasure of presenting a paper based on my undergraduate thesis, which investigates issues of gender and sexual predation in Heavy Metal Music Cultures. The opportunity to present accompanied an award by the Council Heads of Higher Music Education, which focuses on Irish Undergraduate Thesis in Music. As a consequence, the panel to which I contributed featured diverse topics.

Though my paper shed light on an intense and unsettling topic, it appeared to engage the attendees of the panel. Part of its appeal was distinctness among the conference, as it was one of few Popular Musicology Papers, contrasted with papers analysing Art Music, Traditional Music, or Ethnomusicology. As a result, the post-presentation questions revealed interesting discussion, some of which proceeded into the following break. The process of discussing the topic and conclusions of my thesis gave me the feeling of a firm knowledge in an area I had spent a considerable amount of time researching. There was something affirming in having my comparative expertise tested in such a way. I found myself excited to embark on the journey to acquire a similar knowledge through my Master’s thesis. Yet, as big a role as my own presentation played for my conference experience, the panels and speakers were equally remarkable.

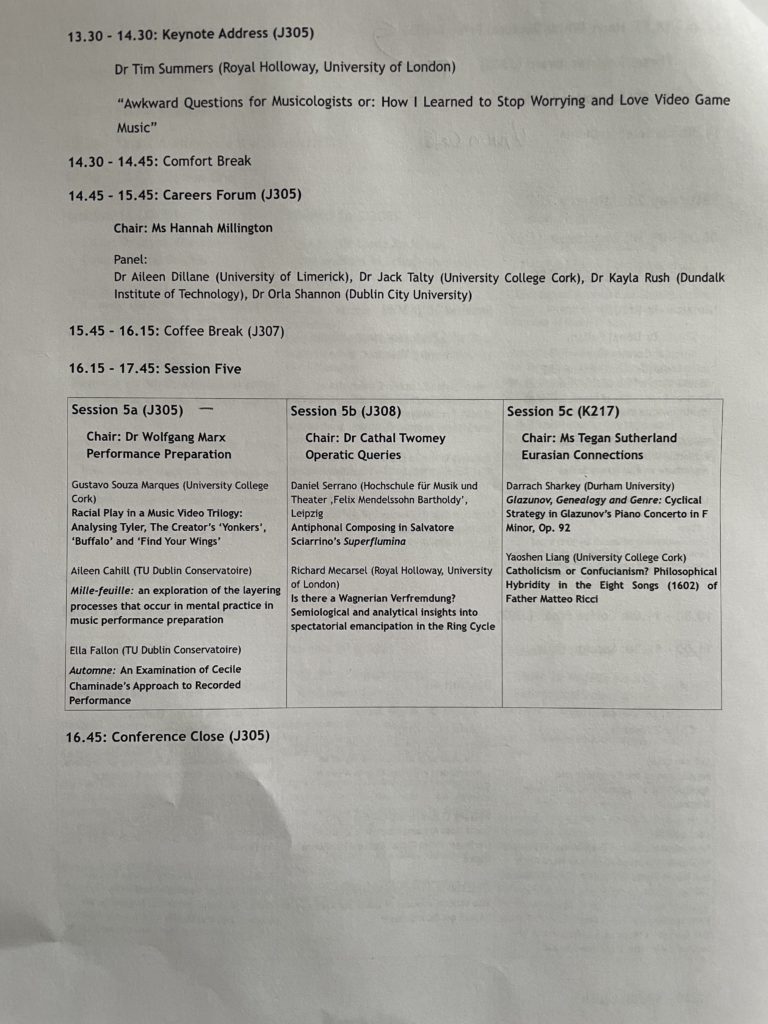

I attended a variety of panels with a diversity of papers. A common theme revealed itself across some papers and the keynote address. In a world peopled with increasingly advancing technologies, we are faced with more and more opportunities to marry artistic practice with technology. The distinction between traditions and forms, practices and mediums dissolve and blur.

A panel on Compositional Studies broached this theme. Yue Song, a composer and postgraduate researcher at TU Dublin Conservatoire, presented a fascinating paper. She discussed her compositional method in a project, which focuses on pieces for bass clarinet, enhanced by digitally created sound effects. To trigger the effects in live performance, the musician utilises a sensor triggered by a few natural movements and cues. With sensors more advanced and finely tuned than traditional live effect technology (such as guitar pedals), the project suggested an advanced synthesising of technology with artistic practice.

Picking up the goal of synthesis in a different context, Daniel Vives-Lynch of Trinity College pondered the problem of synthesising European Art Music with Irish Traditional Music. His concern lied with a true synthesis, rather than a “cultural colonisation” in the way of interpolating surface elements of traditional music into Art pieces. Although the two papers were different in approach and topic, they share a similarity at the core. As artists have access to wider inspirations through the power and connectivity of the Internet, they have to consider how to respectfully blend these influences and traditions. Be it in regards to technology or genre (be it musical or literary), the blurring of forms requires careful consideration and intent.

The Keynote address displayed a similar occupation with the broadening and change of mediums, from a critic’s perspective. Dr Tim Summers, University of London, delivered this engaging address, entitled “Awkward Questions for Musicologists or: how I learned to stop worrying and love Video game Music”. While focusing on Video Games in a Musicological context, Dr Summers confronted the audience with self-reflective questions suitable for any academic that approaches a comparatively new medium, like video games.

His questions encompassed both the material contexts to consider, such as the inherently subjective experience of a video game, as well as the traps of fallacious narratives. Strikingly, he referred to problems of authorial intent within a collaborative medium.

In the case of most video games, there are numerous agents working on music or narrative at any given point. Furthermore, there have been historically cases of marginalised composers not receiving credit or being credited under pseudonyms. This frequently leaves an uncertain space of authorship.

An increasing application of auteur theory to the medium of video games, as it becomes accepted as an art form, only furthers this problem. According to the address, the pitfalls of the auteur present one fallacy among many narratives. Dr Summers further disparages the construction of teleological narratives, narratives that conflate improvement with assimilation to more traditional forms. As an example, he critiques the idea that modern Video Game Scores have evolved in quality simply because they frequently resemble European Art music, unlike earlier 8-bit music. Critics may also have to consider the ideas and narratives they import by using terms and analytical tools conceived for other mediums.

Overall, this address delivered a challenge to anyone who dissects and analyses media, questioning the biases and assumptions we as critics bring to the table. As such, it was a highlight of the conference. Due to the thought-provoking ideas of the speakers and presenters, I did not only leave the conference with an academic achievement under my belt, but a reevaluated perspective and renewed passion for musicological and literary academia.