Frank Herbert’s Dune is an influential and seminal work of Science Fiction. With a cult classic adaptation by director David Lynch and an on-going high budget interpretation by Denis Villeneuve, the books of the Dune universe have amassed a sizeable following. Notably, in memetic responses, fans have iconised a particular element of the universe’s lore: The Sand-worms.

Worms feature across serious and joking fan engagement with the books. The 1976 sequel Children of Dune often is a focus of this engagement, because one of its protagonists transforms into a giant immortal sand-worm-human hybrid being. However, this culture around Dune’s worms also draws on the initial 1965 novel. An awareness of this floated in my mind when I read Dmitry Glukhovsky’s post-apocalyptic horror novel Metro 2033. As intrepid protagonist Artyom stumbled upon a cannibalistic cult that worships a giant worm god, that awareness drilled itself to the front of my thoughts. I could not help but wonder, is there a relationship here? And why worms?

It is hard to say if Dmitry Glukhovsky was inspired by Dune’s Sand-worms. Regardless, it would not be surprising if the influence were direct, as one may point to many similarities. Both Sand-worms and The Worm God are worms blown out of proportion, gigantic. They are divine and primordial beings. Although Metro 2033’s Worm God is explicitly a fiction within the novel, it is depicted and lent credence as an old, unfathomable being of creation. The worm, within the cult’s beliefs, created the world and the tunnels, gifting authority over the world to humans in its absence. The worm god is older than humanity, and implied to outlast it, punishing humans for their environmental destruction and violence.

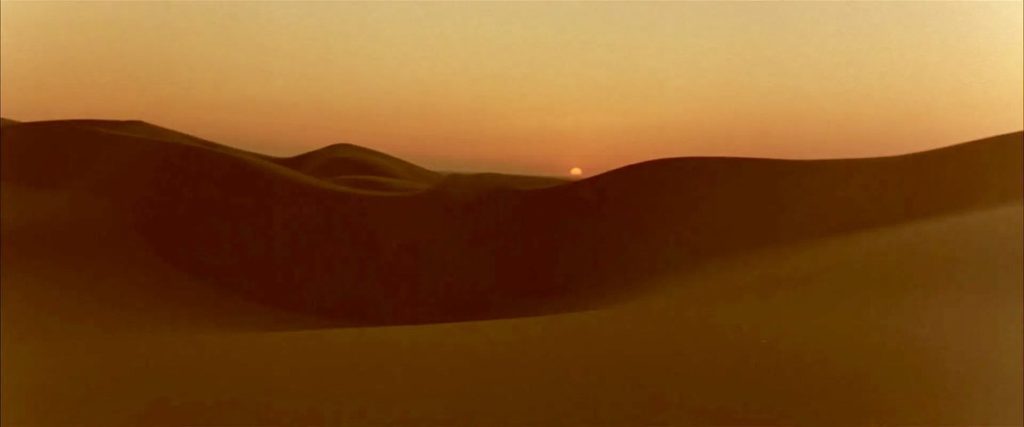

Dune depicts its Sand-worms from two perspectives. Initially, we learn about them from a colonising perspective. The houses that occupy the desert planet Arrakis see the Sand-worms as threats to human mining of the planet’s natural resource, Spice. The noble houses of Dune’s world desire Spice as a highly valuable industrial resource primarily, as it is used for space travel. Throughout the novel the protagonist Paul transitions from allegiance with noble houses to allegiance with the native inhabitants of the planet and desert-people, the Fremen. Our knowledge of Spice and the Sand-worms realigns accordingly.

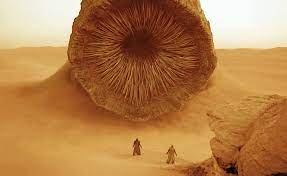

Initially, the reader learns of Spice as a hallucinatory substance, involved in the Fremen’s rich and nuanced religious rituals. Ultimately, this shift from industrial to spiritual extends to the worms. The novel reveals that the Fremen revere the Worms as Gods, and that the Sand-worms create the Spice. Just as Metro 2033’s worm god, the Sand-worms are ambiguous, ancient forces of creation. The Fremen, unlike their industrialised colonisers, do not have adversarial relationships with the Sand-worms. An important Fremen rite includes the riding of a Sand-worm.

The Sand-worms form part of a contrasting approach to technology and nature. The Fremen operate on minimal technology and are well adjusted to their desert environment, without becoming ‘noble-savage’ stereotypes. Their counterparts, industrialised oppressive rulers, on the other hand, are aligned with an idea of industrialised modernity. They are at odds with the desert and view the natural environment as an exploitable resource.

Worms as a force of nature and environment, opposite to technology, persist similarly in Metro 2033. The old man who invents the Worm religion creates it as anti-technology, demonising modernised man and his environmental destruction. The worship of the worm God includes ceding agency to a natural primordial force, and atoning for mankind’s scarring of nature. The cult rejects technology in their life and returns to pre-modern technologies such as bow and arrows. They present one of the only factions in the novel without guns, displaying active hostility towards them.

Here we have a core similarity then: Worms in both works are powerful agents of the natural world. They are counter points of agency, aligned with the environment and primordial, pre-human creation. It is worth pointing out that the portrayal of their people differs: the reader will automatically sympathise less with the cannibal cult than with an exploited and hunted indigenous people. But this does not diminish that their respective worms seem to communicate the same message about and relationship with natural forces. That kind of relationship resonates in these two works that engage with the apocalypse, though be it in different ways.

But, while this answers my first question- is there a relationship-, my second question remains. Why worms? I can only theorise, but one key possibility stands out to me. Let me take you on my little conspiratorial route.

Worms, unlike other animals, have a bigger capacity for the alien. In Dune, they are quite literally alien, in the sense of extra-terrestrial. But worms are also alien in the sense of being estranged from the human, or what we can personalise. Humans generally seem to more easily anthropomorphise or generate empathy for certain animals. I would boldly generalise that the more features humans share with an animal, the easier they empathise or find the animal aesthetically pleasing. Insects generally receive less empathy than most other animals with their exoskeletons, many legs, too many eyes, or other features many humans find revolting.

Worms are slimy and squishy, flexible. They are, unlike us, not vertebrate, without a backbone. They have neither interior skeletons nor exoskeletons. Most notably, they have no eyes. Many design theories often argue that eyes in particular aid humans to identify and humanise creatures. One could look at District 9’s choice to give its alien protagonist, with whom the viewer is meant to sympathise, child-like eyes, big and round. On the other hand, the Alien Franchise designs its dangerous Xenomorphs completely without eyes. If we appropriate this theory for our eye-less worms then, one may argue that worms are in many ways a type of life that is aesthetically and conceptually far enough removed from humans to make them prime candidates for alien beings.

Commonly, we also associate worms with the earth in which they life buried. There is a link to death here as well, through expressions associated with death that feature worms: “Counting worms” or “Food for worms”/ ”Worm Food”. Of course, worms cannot even leave behind in their death the bones whose company they keep. If the two discussed works posit their worms as outlasting humanity, so do some of our English common expressions.

Worms are beings, then, which can be easily made alien and associated with the most primal natural element, the Earth. They carry connotations of outlasting us buried in the deep earth. Dune and Metro 2033 utilise them as an apt tool to tap into our relationship with the Earth and our Environment. These stories imagine primordial forces that are alien to humanity and more long-lasting, creators of the space mankind inhabits, with worms as their willing vessel.

Memetic though it can be, these imaginings are certainly not coincidental and are extremely telling. They glimpse into how stories dissect industrialisation, technology, and modernity, and the role nature and environmental agency must play in those considerations. They tease the fading horizon of humanity and picture the Earth’s alien invertebrate inheritors.