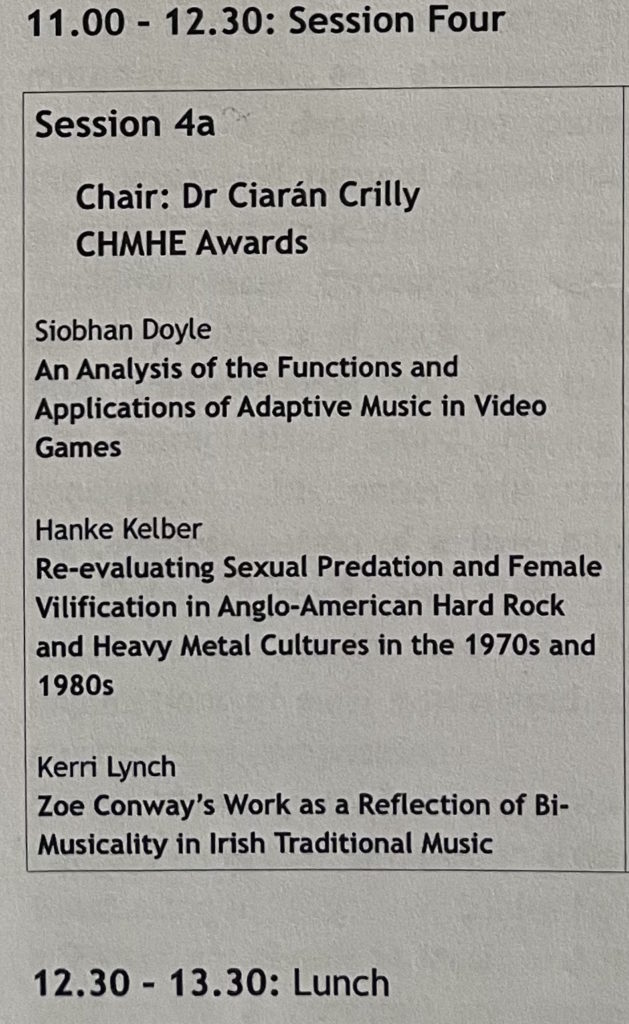

Love can be strange to represent in video games. Outside of dating simulators or other explicitly dedicated games, Role Playing Games (RPGs) such as Bethesda Studio’s iterations of the Elder Scrolls or the post-apocalyptic Fallout series, frequently offer the player choices for romance. As Bethesda is gearing up for the release of their new RPG, Starfield, I want to look closer at systems of romance in previous Bethesda games. Such an examination presents curious results. Romance systems can offer avenues to enjoyment and queer content. But at their core they can also tell us how people approach love in real life.

The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim falls short in its options for romantic companionship. To marry in Skyrim, the player presents a specific artefact to their partner of choice. That spouse then benefits the player in transactional ways, often sharing goods and income. Useful, yes, but not much of a shot at depicting romance. One of Bethesda’s other games, Fallout 4, makes a more earnest effort. The player here can romance most (and any amount) of their companions through dialogue options. These options appear if the companion morally approves of the player’s actions, maximising the companion status. The relationship is then further enhanced through the completion of companion quests, which only surface when the companion trusts the player.

The result of the developed romance mainly consists of occasional romantic dialogue, and cheeky corner animations after sleeping. In a way, this brings us closer to actual love and romance at least; the player has to appeal to their companion through their actions and characterisation. As a result, such romances can be fun to achieve, especially for any players that wish to create queer content in their RPG experience, as all romance-able characters will be attracted to the player regardless of their gender.

Yet, as enjoyable as using these mechanics can be, there is something inherently odd about them. Due to their optional nature, they never affect a player’s gaming experience significantly. Your companions in the end are still a transactional boon as far as the game is concerned. Everything else is left solely to the player’s imagination of a NPC(non-player character) with little dimension. The reality of their emotion and romance bears little depth to the characters and their world. It contributes to the feeling that the world of the game is made for you, the player. It revolves around you, its inhabitants ready to offer quests, be romanced, or shot.

To allude to the concept of the ‘Gay Button’, Romance mechanics are also not a satisfying definite inclusion of queerness, since only the player can initiate queer content. In contrast, I think RPGs without real romancing options can often be much stronger. Games such as Fallout: New Vegas or The Outer Worlds instead give their characters innate sexualities and identities that affect how they interact with the world around them. As a result, the game’s world feels more immersive. The world is made for the player, but it feels like it could exist on its own. That yields bigger benefit to me than creating a virtual romance thought experiment.

Philosophically, the idea of love as something you can achieve, with anyone, with the right kind of lines, resonates uncomfortably with modern dating discussions.

At its most harmless, it reminds me of the way people can talk about online-dating. There is this idea of making love logical, of having a set of lines that guarantees success. In dedicated communities, participants seem to attempt generalised advised about how profiles should look like, or what opening lines will guarantee success. The complexities of attraction and conversational dynamics become streamlined into over-promising codes and guides. This is not to say that anyone can be blamed for investing in this promise. Relationships are difficult, and it is natural to wish for a simpler narrative. But ultimately, they are still oversimplified narratives.

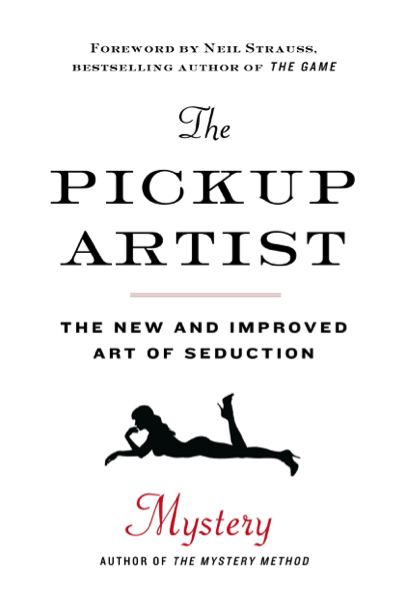

A parallel at its worst, the ideology of Pick Up Artists treats women like an RPG Romance system treats NPCs. They are not given interiority, but reduced to calculable responses and behaviours. It is not uncommon to hear about women’s “programming” by such people. They predict the outcome of certain dialogue lines and ‘openers’ or actions in their ‘game’, not giving much regard to the object of their desire.

But what is the point of such an abstract discussion of a mere fun game mechanic? Well, maybe games replicate life a lot more than we think. Maybe games with one-note Romance systems are not as fun as thoughtful characters because they replicate something that does not help love in real life either. If the media we consume shapes how we interact with the world and people around us, it bears thinking about what fantasies about romance our media sells to us. Love and Romance is complicated, but much more successful when we respect our partners’ feelings and interiority. The temptation to retreat into simpler, classifying narratives provides little benefit. The more depth we allow for, the more we can make out of relationships.